The thin young man sat on the witness

stand, fending off sharp questions by the defense lawyer and trying to

explain how he was sexually abused when he was 16.

Who took off your clothes? attorney Chris Gunter asked.

I did, the witness said.

But you told another investigator he took your clothes off.

No, I did.

The sparring continued and after a few minutes, the witness lost it.

“It doesn’t matter who took — I can’t do this — I can’t testify anymore.” He jumped up and rushed out of the courtroom.

Prosecutor Mary Farrington hurried after him. The jury was quickly ushered out.

It was an intense moment, one of many during the four-week trial of Charles Fischer, a former Austin State Hospital psychiatrist convicted Wednesday of sexually abusing three of his adolescent patients at the facility. Fischer was found guilty of 11 felonies, including four counts of sexual assault of a child.

Who took off your clothes? attorney Chris Gunter asked.

I did, the witness said.

But you told another investigator he took your clothes off.

No, I did.

The sparring continued and after a few minutes, the witness lost it.

“It doesn’t matter who took — I can’t do this — I can’t testify anymore.” He jumped up and rushed out of the courtroom.

Prosecutor Mary Farrington hurried after him. The jury was quickly ushered out.

It was an intense moment, one of many during the four-week trial of Charles Fischer, a former Austin State Hospital psychiatrist convicted Wednesday of sexually abusing three of his adolescent patients at the facility. Fischer was found guilty of 11 felonies, including four counts of sexual assault of a child.

It’s still unclear how many boys Fischer

might have abused during his time with the state. A 2011 investigation

by Adult Protective Services turned up 10 possible cases in state

hospitals: nine at Austin State Hospital, one at Waco Center for Youth.

Still more came forward after the doctor was indicted in 2012.

The trial did more than send Fischer to prison. It shed light on a system that allowed him to repeatedly abuse the severely mentally ill adolescent boys in his care for more than two decades, even after several youths had accused him of molesting them.

He met with kids with severe sexual problems alone at night, on weekends and off campus. No one said anything.

He shut and locked his office door with patients inside, even after he was told not to. Administrators let it go.

He admitted bringing a teen to his office at Waco Center for Youth, taking off some of his own clothes, examining the boy’s penis in a locked administration building and the superintendent of the facility told him not to come back. Yet he was allowed to keep working at Austin State Hospital.

State officials say they’ve made big changes since the Fischer case blew up five years ago, when the Austin American-Statesman did a series of stories identifying lapses in the hospital and child welfare systems.

The trial did more than send Fischer to prison. It shed light on a system that allowed him to repeatedly abuse the severely mentally ill adolescent boys in his care for more than two decades, even after several youths had accused him of molesting them.

He met with kids with severe sexual problems alone at night, on weekends and off campus. No one said anything.

He shut and locked his office door with patients inside, even after he was told not to. Administrators let it go.

He admitted bringing a teen to his office at Waco Center for Youth, taking off some of his own clothes, examining the boy’s penis in a locked administration building and the superintendent of the facility told him not to come back. Yet he was allowed to keep working at Austin State Hospital.

State officials say they’ve made big changes since the Fischer case blew up five years ago, when the Austin American-Statesman did a series of stories identifying lapses in the hospital and child welfare systems.

Those changes include installing more than

500 cameras in the 10 state psychiatric hospitals, increasing scrutiny

of staffers accused of sexual abuse, creating a database to track

patterns of abuse allegations and working more closely with Adult

Protective Services in such investigations.

The state also changed its policy on retention of records and now keeps child abuse investigations for 20 years instead of five so patterns can be identified.

“We’ve made many improvements since 2011, and we’re always looking for ways to make our patients safer and to reduce the risk for abuse,” said Christine Mann, spokeswoman for the Department of State Health Services, which oversees the hospitals.

But mental health advocates who work in the hospitals say that one of the biggest problems identified in the Fischer case still exists: a culture that protects professionals and doubts patients because of their mental illnesses. And that, they say, leaves patients vulnerable.

“Although some changes were made, I do not believe the Fischer thing has made patients safer because the culture at the hospitals has not changed,” said Cindy Gibson with Disability Rights Texas, a federally designated legal protection and advocacy group for people with disabilities.

Disability Rights often reviews Adult Protective Services investigations and is sometimes frustrated by the results, Gibson said. Staffers often get the benefit of the doubt in cases where there is no physical evidence, even when numerous patients claim to have seen the abuse, she said.

People often equate mental illness with unreliability, as Fischer’s defense lawyers attempted to do during his trial. An expert witness for the prosecution countered that having a psychiatric disorder — even a severe one — doesn’t necessarily mean a break with reality altogether.

In the courtroom, while confronting the man on the stand, Gunter emphasized that Fischer’s accusers were too unstable to be trusted. If it really happened, he asked the witness, why didn’t you tell someone?

The man’s answer was simple.

“I’m 16 and in a state hospital. I didn’t think anyone would believe me.”

The state also changed its policy on retention of records and now keeps child abuse investigations for 20 years instead of five so patterns can be identified.

“We’ve made many improvements since 2011, and we’re always looking for ways to make our patients safer and to reduce the risk for abuse,” said Christine Mann, spokeswoman for the Department of State Health Services, which oversees the hospitals.

But mental health advocates who work in the hospitals say that one of the biggest problems identified in the Fischer case still exists: a culture that protects professionals and doubts patients because of their mental illnesses. And that, they say, leaves patients vulnerable.

“Although some changes were made, I do not believe the Fischer thing has made patients safer because the culture at the hospitals has not changed,” said Cindy Gibson with Disability Rights Texas, a federally designated legal protection and advocacy group for people with disabilities.

Disability Rights often reviews Adult Protective Services investigations and is sometimes frustrated by the results, Gibson said. Staffers often get the benefit of the doubt in cases where there is no physical evidence, even when numerous patients claim to have seen the abuse, she said.

People often equate mental illness with unreliability, as Fischer’s defense lawyers attempted to do during his trial. An expert witness for the prosecution countered that having a psychiatric disorder — even a severe one — doesn’t necessarily mean a break with reality altogether.

In the courtroom, while confronting the man on the stand, Gunter emphasized that Fischer’s accusers were too unstable to be trusted. If it really happened, he asked the witness, why didn’t you tell someone?

The man’s answer was simple.

“I’m 16 and in a state hospital. I didn’t think anyone would believe me.”

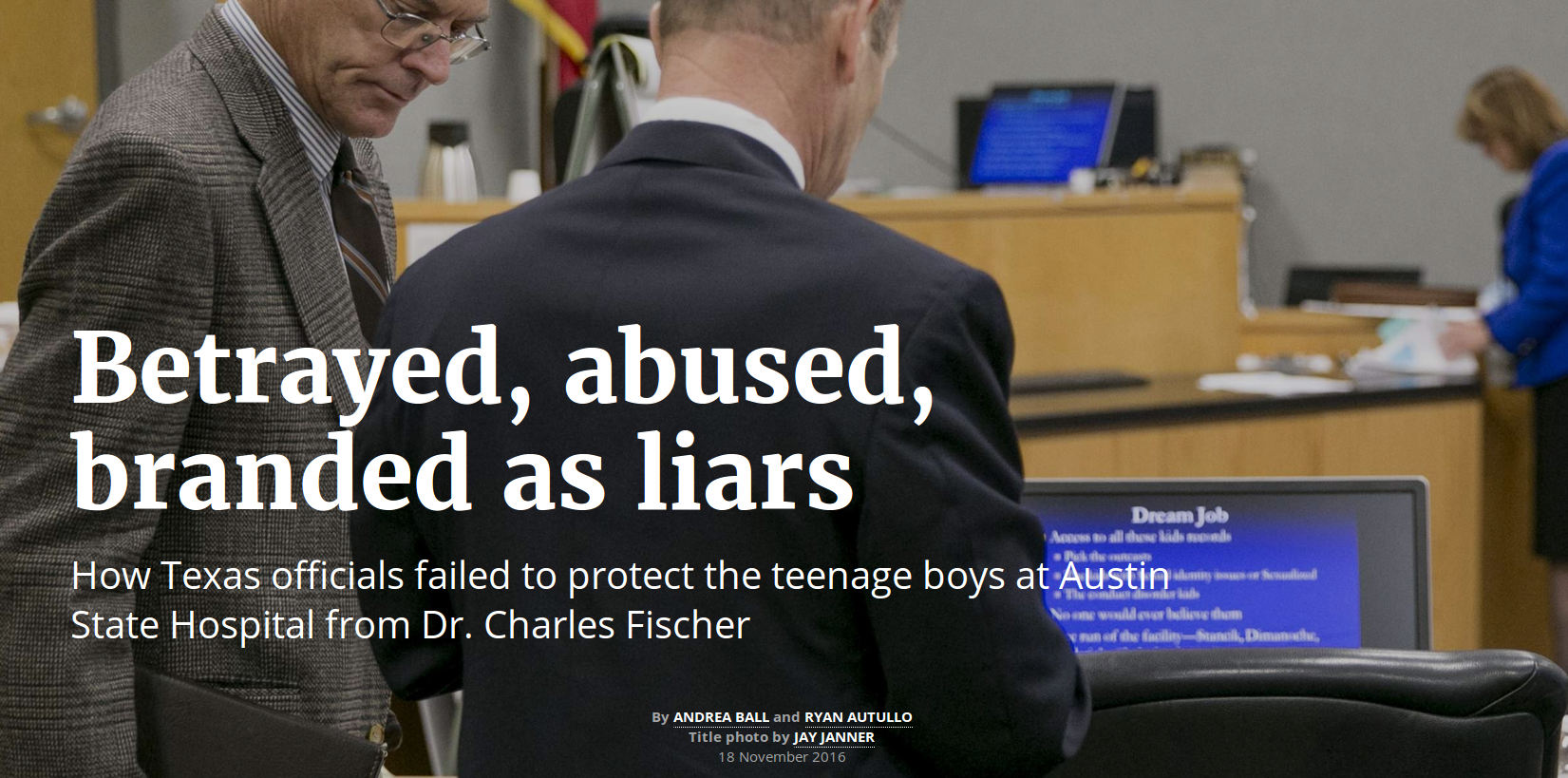

Charles Fischer sat alone at the defense

table in Judge Karen Sage’s courtroom, staring straight ahead

expressionlessly for more than an hour as his lawyers met with the judge

in chambers.

It had been five years since the once-respected psychiatrist had been fired from Austin State Hospital after being accused of sexually abusing his former patients. Now, clad in the same brown tweed jacket day after day, he was facing a jury of his peers on the eighth floor of the Blackwell-Thurman Criminal Justice Center.

Fischer, who was born in San Antonio, attended the University of Texas and went to medical school at UT Health Science Center, according to his application for state employment.

It was 1990 when the doctor came to Austin State Hospital, a state-run psychiatric facility for people with major mental illnesses such as depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. He worked on the children’s unit.

It had been five years since the once-respected psychiatrist had been fired from Austin State Hospital after being accused of sexually abusing his former patients. Now, clad in the same brown tweed jacket day after day, he was facing a jury of his peers on the eighth floor of the Blackwell-Thurman Criminal Justice Center.

Fischer, who was born in San Antonio, attended the University of Texas and went to medical school at UT Health Science Center, according to his application for state employment.

It was 1990 when the doctor came to Austin State Hospital, a state-run psychiatric facility for people with major mental illnesses such as depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. He worked on the children’s unit.

The kids were young but deeply troubled.

Some heard voices or saw things that weren’t there. Some were seriously

depressed, others angry and violent. They were the kind of patients

Fischer seemed to specialize in. He took on the most disturbed children,

something his peers appreciated and admired.

To those who knew him, Fischer was the ideal doctor. He worked nights, weekends and holidays. He seemed nice enough, if guarded about his private life.

Dr. Satish Bhatt, a hospital psychiatrist who considered Fischer a friend and mentor, said he never saw Fischer do anything inappropriate with patients.

“He was very professional,” Bhatt told the jury.

In 1992, Waco Center for Youth – another state psychiatric hospital – needed a doctor to fill in at the facility several times a week. Fischer stepped in to help.

But a problem arose when Fischer started hanging out with the boys wearing skimpy pink shorts, former Waco nurse Dennis Edwards told the jury. That didn’t escape the notice of youth, many of whom were already acting out sexually.

“There was a lot of chatter going on about his attire,” Edwards said.

Edwards reported him and the doctor stopped wearing those shorts.

Then came the first compliant against Fischer.

The Waco youth was 16 years old. He had serious aggression problems and engaged in inappropriate sexual behavior. Just days earlier he had been diagnosed with a sexually-transmitted disease and one night, he went to Fischer for a checkup, the now-adult testified under oath.

Fischer asked the teen if he wanted to be examined in the unit or in Fischer’s office for more privacy.

They went to the administration building and entered an office, the witness testified. Fischer locked the door and pulled off his sweatshirt and sweatpants, saying he was hot, and then examined the boy’s penis, he testified.

Fischer let the teen look at pornography and exposed himself, the witness told the jury. Afterward, Fischer pleaded with him to not tell.

“You could say he was begging,” the man told the jury.

To those who knew him, Fischer was the ideal doctor. He worked nights, weekends and holidays. He seemed nice enough, if guarded about his private life.

Dr. Satish Bhatt, a hospital psychiatrist who considered Fischer a friend and mentor, said he never saw Fischer do anything inappropriate with patients.

“He was very professional,” Bhatt told the jury.

In 1992, Waco Center for Youth – another state psychiatric hospital – needed a doctor to fill in at the facility several times a week. Fischer stepped in to help.

But a problem arose when Fischer started hanging out with the boys wearing skimpy pink shorts, former Waco nurse Dennis Edwards told the jury. That didn’t escape the notice of youth, many of whom were already acting out sexually.

“There was a lot of chatter going on about his attire,” Edwards said.

Edwards reported him and the doctor stopped wearing those shorts.

Then came the first compliant against Fischer.

The Waco youth was 16 years old. He had serious aggression problems and engaged in inappropriate sexual behavior. Just days earlier he had been diagnosed with a sexually-transmitted disease and one night, he went to Fischer for a checkup, the now-adult testified under oath.

Fischer asked the teen if he wanted to be examined in the unit or in Fischer’s office for more privacy.

They went to the administration building and entered an office, the witness testified. Fischer locked the door and pulled off his sweatshirt and sweatpants, saying he was hot, and then examined the boy’s penis, he testified.

Fischer let the teen look at pornography and exposed himself, the witness told the jury. Afterward, Fischer pleaded with him to not tell.

“You could say he was begging,” the man told the jury.

But he did tell.

Fischer told both the police and an Adult Protective Services investigator that he had brought the teen to an office in the administration building after hours (he said the boy wanted privacy), taken off his own sweatpants (he was wearing shorts underneath), and examined the teen with his bare hands (he said the exam room was locked and he didn’t have sterile gloves).

But the teen had credibility problems and there were no eyewitnesses, former investigator Richard Fogleman told the jury.

Charles Locklin, superintendent of Waco Center for Youth at the time, told Fischer not to return until the complaint was resolved. He called the state medical director and told him what was happening.

“He sort of poo-pooed the whole thing, saying that doesn’t sound right,” Locklin recalled. “I said, ‘You can investigate if you want but I’m very firm — he’s not coming back here.’”

The police investigated but no charges were filed. Adult Protective Services deemed the allegation unfounded. But while Fogleman did not confirm the accusation, he did raise a red flag about Fischer meeting alone outside of normal business hours with boys who had sexual issues.

“I recommended that not be allowed as a practice,” Fogleman said.

Despite being cleared, Fischer never returned.

Fischer told both the police and an Adult Protective Services investigator that he had brought the teen to an office in the administration building after hours (he said the boy wanted privacy), taken off his own sweatpants (he was wearing shorts underneath), and examined the teen with his bare hands (he said the exam room was locked and he didn’t have sterile gloves).

But the teen had credibility problems and there were no eyewitnesses, former investigator Richard Fogleman told the jury.

Charles Locklin, superintendent of Waco Center for Youth at the time, told Fischer not to return until the complaint was resolved. He called the state medical director and told him what was happening.

“He sort of poo-pooed the whole thing, saying that doesn’t sound right,” Locklin recalled. “I said, ‘You can investigate if you want but I’m very firm — he’s not coming back here.’”

The police investigated but no charges were filed. Adult Protective Services deemed the allegation unfounded. But while Fogleman did not confirm the accusation, he did raise a red flag about Fischer meeting alone outside of normal business hours with boys who had sexual issues.

“I recommended that not be allowed as a practice,” Fogleman said.

Despite being cleared, Fischer never returned.

Long list of complaints

Kids complained consistently about Fischer

over the next 20 years. Fischer denied all of the allegations, and none

resulted in professional discipline or criminal charges. A 2002 grand jury scrutinized allegations against Fischer, but he was not indicted and continued practicing.

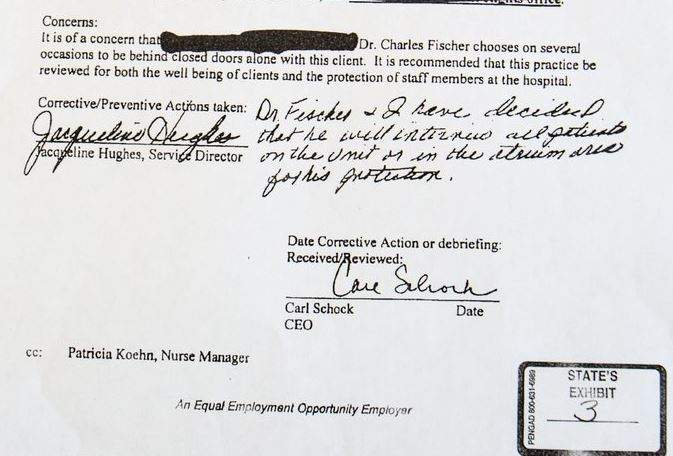

In 2004, after yet another allegation, Austin State Hospital’s former superintendent wrote in a memo that the doctor’s practice of meeting behind closed doors with one particular patient should be reviewed “for the well-being of clients and the protection of staff members.”

Fischer’s direct boss, Jacqueline Hughes, wrote on the memo that “Dr. Fischer and I have decided that he will interview all patients on the unit or in the atrium area for his protection.”

In 2004, after yet another allegation, Austin State Hospital’s former superintendent wrote in a memo that the doctor’s practice of meeting behind closed doors with one particular patient should be reviewed “for the well-being of clients and the protection of staff members.”

Fischer’s direct boss, Jacqueline Hughes, wrote on the memo that “Dr. Fischer and I have decided that he will interview all patients on the unit or in the atrium area for his protection.”

Then, according to trial testimony, Hughes

ordered an employee with an office near Fischer’s to spy on him and make

sure he abided by the rule. That employee — Cathy Almaraz — told jurors

that he did keep it open at first. But over the course of six months,

he closed it little by little until finally he started shutting it all

the way again, she said.

Amaraz said she reported that to Hughes but nothing changed.

Adult Protective Services is the state agency that investigates abuse and neglect of patients at the state psychiatric hospitals. Its investigators interview witnesses, examine evidence, research records and decide whether the allegations are true.

The evidence doesn’t have to meet the “reasonable doubt” standard of a criminal trial. Instead, it must meet the “preponderance of the evidence” measure, meaning it is more likely than not that the allegation is true.

Physical evidence such as the existence and characteristics of injuries, documentary evidence and expert testimony can help establish preponderance for physical abuse or sexual abuse, said Patrick Crimmins of the Department of Family and Protective Services, which oversees Adult Protective Services.

Strictly speaking, investigators don’t need an eyewitness to confirm that abuse happened. But throughout the trial, investigators cited the lack of them as a problem.

In 2004, former investigator Stellamaris Bonney was assigned to check out an allegation that Fischer had sexually abused a 14-year-old patient. She’d confirmed much of what the boy said: that Fischer had taken him to his office and locked the door, that the blinds were closed, that there was a bathroom nearby and that there was a jar of Vaseline in the doctor’s desk drawer.

Amaraz said she reported that to Hughes but nothing changed.

Adult Protective Services is the state agency that investigates abuse and neglect of patients at the state psychiatric hospitals. Its investigators interview witnesses, examine evidence, research records and decide whether the allegations are true.

The evidence doesn’t have to meet the “reasonable doubt” standard of a criminal trial. Instead, it must meet the “preponderance of the evidence” measure, meaning it is more likely than not that the allegation is true.

Physical evidence such as the existence and characteristics of injuries, documentary evidence and expert testimony can help establish preponderance for physical abuse or sexual abuse, said Patrick Crimmins of the Department of Family and Protective Services, which oversees Adult Protective Services.

Strictly speaking, investigators don’t need an eyewitness to confirm that abuse happened. But throughout the trial, investigators cited the lack of them as a problem.

In 2004, former investigator Stellamaris Bonney was assigned to check out an allegation that Fischer had sexually abused a 14-year-old patient. She’d confirmed much of what the boy said: that Fischer had taken him to his office and locked the door, that the blinds were closed, that there was a bathroom nearby and that there was a jar of Vaseline in the doctor’s desk drawer.

But when she confronted the doctor, she

couldn’t even bring herself to ask him about the Vaseline she could see

in his cracked desk drawer. Fischer was defensive and haughty, telling

her that he locked the door for privacy, Bonney told the jury. Nothing

he told her made sense, she said.

But there were no eyewitnesses and she felt she felt helpless to do anything, she said, recalling that she sat in her car in the hospital parking lot and cried after the interview.

“He’s the doctor, and I’m just the investigator,” she said.

That gets to the heart of what Gibson, of Disability Rights Texas, says is a problem at all the state hospitals.

“People see what they want to see, and people who are in positions of authority are granted a credibility that they don’t necessarily earn and, in some cases, don’t deserve,” she said.

In May 2011, an unusual allegation of abuse came in to Adult Protect Services.

A young man had told his therapist that he had been abused by Fischer in 2003, eight years earlier. The old case had never been reported to Adult Protective Services.

He told Adult Protective Services that when he was a teenager, Fischer had touched him and masturbated in front of him numerous times at the hospital. In Fischer’s trial, his mother said she had tried to report the abuse but had been rebuffed by an Austin State Hospital social worker, who said: “He wouldn’t do anything like that. He has a family, and he’s married.” (The social worker denied this on the stand.)

Fischer has never been married.

But there were no eyewitnesses and she felt she felt helpless to do anything, she said, recalling that she sat in her car in the hospital parking lot and cried after the interview.

“He’s the doctor, and I’m just the investigator,” she said.

That gets to the heart of what Gibson, of Disability Rights Texas, says is a problem at all the state hospitals.

“People see what they want to see, and people who are in positions of authority are granted a credibility that they don’t necessarily earn and, in some cases, don’t deserve,” she said.

In May 2011, an unusual allegation of abuse came in to Adult Protect Services.

A young man had told his therapist that he had been abused by Fischer in 2003, eight years earlier. The old case had never been reported to Adult Protective Services.

He told Adult Protective Services that when he was a teenager, Fischer had touched him and masturbated in front of him numerous times at the hospital. In Fischer’s trial, his mother said she had tried to report the abuse but had been rebuffed by an Austin State Hospital social worker, who said: “He wouldn’t do anything like that. He has a family, and he’s married.” (The social worker denied this on the stand.)

Fischer has never been married.

An old case without witnesses could have

devolved into yet another case of he said, he said. Instead,

investigators searched for other patients who had accused Fischer over

the years. They talked to the Waco Police Department officers who had

investigated the 1992 allegation, and they talked to an expert about the

behavior of adult sex offenders and their patterns.

They read patient medical records, reviewed old investigations. And then they talked to Fischer.

As with all the other times he had been accused, Fischer was allowed to continue working with patients during the investigation. He had been ordered to conduct therapy outside of his office and abide by other rules.

During his interview with investigators, Fischer initially seemed relaxed and cooperative, former investigator Laura Thetford told the jury. Then, as the conversation progressed, Fischer became visibly upset, breathing heavily and baring his teeth at one point.

“Instead of being surprised by the allegations, it was almost anger instead,” said Thetford, who is now an attorney.

Five months after launching its investigation, Adult Protective Services confirmed the 2003 abuse allegation. The report also confirmed the abuse of another teen in 2005 and 2006.

They read patient medical records, reviewed old investigations. And then they talked to Fischer.

As with all the other times he had been accused, Fischer was allowed to continue working with patients during the investigation. He had been ordered to conduct therapy outside of his office and abide by other rules.

During his interview with investigators, Fischer initially seemed relaxed and cooperative, former investigator Laura Thetford told the jury. Then, as the conversation progressed, Fischer became visibly upset, breathing heavily and baring his teeth at one point.

“Instead of being surprised by the allegations, it was almost anger instead,” said Thetford, who is now an attorney.

Five months after launching its investigation, Adult Protective Services confirmed the 2003 abuse allegation. The report also confirmed the abuse of another teen in 2005 and 2006.

‘They were finally believed’

The victims filed before the jury, one by one, each with his own story.

He showed me porn. He touched me. He gave me fellatio. He made me have sex with him.

“To give you an idea of how young I was, I was afraid I’d get pregnant,” said one victim, the only witness who was not a former patient of Fischer’s. The witness said he was 7 when the abuse began. Fischer was a teenager.

He showed me porn. He touched me. He gave me fellatio. He made me have sex with him.

“To give you an idea of how young I was, I was afraid I’d get pregnant,” said one victim, the only witness who was not a former patient of Fischer’s. The witness said he was 7 when the abuse began. Fischer was a teenager.

Then came the co-workers, investigators and police officers.

The seven-woman, five-man jury’s verdict came down to the credibility of the victims, said juror Amy Smith. They believed the witness who ran off the stand. They believed the witness who said he was abused when Fischer was a teen. While they remained skeptical of the testimony, they ultimately believed the psychiatrist had a type of victim and a pattern of behavior.

“They remembered so many details from the past and a lot of things they said coincided with expert witnesses or other victims,” Smith said.

Twenty-four years after the first sexual abuse allegation from Waco Center for Youth was lodged against him, Fischer was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

“We’re really happy for the victims,” Smith said. “They were finally believed.”

The seven-woman, five-man jury’s verdict came down to the credibility of the victims, said juror Amy Smith. They believed the witness who ran off the stand. They believed the witness who said he was abused when Fischer was a teen. While they remained skeptical of the testimony, they ultimately believed the psychiatrist had a type of victim and a pattern of behavior.

“They remembered so many details from the past and a lot of things they said coincided with expert witnesses or other victims,” Smith said.

Twenty-four years after the first sexual abuse allegation from Waco Center for Youth was lodged against him, Fischer was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

“We’re really happy for the victims,” Smith said. “They were finally believed.”

Charles Fischer is led away by a Travis County sheriff’s deputy after being sentenced to 40 years

at the Blackwell-Thurman Criminal Justice Center on Thursday November 17, 2016.

The originial post in The Statesman has many more pictures and witness testimony.

No comments:

Post a Comment