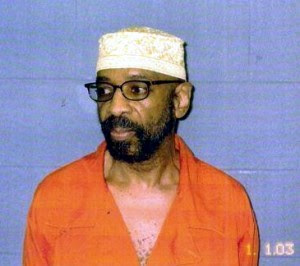

After 33 Years in Solitary Confinement, Former Black Panther Russell Shoatz Will Have His Day in Court

by Jack Denton Russell

"Maroon" Shoatz, a former Black Panther who escaped from Pennsylvania

prisons twice in the 1970s, was held in solitary confinement for nearly

thirty-three years, including twenty-two consecutive years, from 1991 to

2014. During that time, Shoatz was in confined to his cell, in complete

social isolation, for 23-24 hours a day. He contends that his time in

solitary has lead him to develop severe mental health issues, including

chronic depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and more--and that the

length of time he was held in isolation was based, at least in part, on

his political beliefs. But as of last month, Shoatz is one step closer

to potential legal remedy for his decades in solitary confinement.

Russell

"Maroon" Shoatz, a former Black Panther who escaped from Pennsylvania

prisons twice in the 1970s, was held in solitary confinement for nearly

thirty-three years, including twenty-two consecutive years, from 1991 to

2014. During that time, Shoatz was in confined to his cell, in complete

social isolation, for 23-24 hours a day. He contends that his time in

solitary has lead him to develop severe mental health issues, including

chronic depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and more--and that the

length of time he was held in isolation was based, at least in part, on

his political beliefs. But as of last month, Shoatz is one step closer

to potential legal remedy for his decades in solitary confinement.

Since

2013, Shoatz has been engaged in a legal suit against the secretary of

the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections and the warden of State

Correctional Institution at Greene (SCI Greene). The suit alleges that

Shoatz’s Eighth Amendment right to be protected from cruel and unusual

punishment was violated by the extreme duration and conditions of his

stay in solitary confinement, and that his Fourteenth Amendment due

process rights were violated by the prison’s administrative review

process, which Shoatz’s lawyers say made his release from solitary

confinement back into the general prison population nearly impossible.

On

February 12th, federal Judge Cynthia Reed Eddy ruled that the civil

suit will go to trial in the US District Court in Western Pennsylvania.

The case had been up for a potential pre-trial ruling known as summary

judgment. Both Shoatz and the defendants, Wetzel and Folino, had filed

opposing motions for a summary judgment. In her denial of summary

judgment, Judge Eddy wrote that while Shoatz and the Department of

Corrections are in agreement about Shoatz’s criminal history and the

duration of his solitary confinement, “beyond these facts, the parties

agree on little else.” She also noted that the Supreme Court, in Hutto v. Finney,

has expressed concern about the possible unconstitutionality of

solitary confinement, “depending on the duration of the confinement and

the conditions thereof.”

Shoatz’s

case is not a class action suit, so any eventual trial decision will

only apply to him. However, the precedent that the case will set could

have wide reverberations for the 80,000 to 100,000 Americans who are

still held in solitary confinement, many for long periods of time--and

most without the benefit of the type of diligent legal counsel that

Shoatz has recently had. Shoatz’s case has avoided a pre-trial dismissal

on the grounds of technicalities, unlike thousands of other similar

cases brought forth without representation. Such dismissals have been

extremely common since the passing of the 1995 Prison Litigation Reform

Act, which makes it extremely difficult for imprisoned people to sue the

government.

One

of Shoatz’s lawyers, Bret Grote of the Abolitionist Law Center, was

unsurprised that Judge Eddy chose not to give a final ruling without

allowing the case to go to trial. “I’m not surprised she denied our

motion [for summary judgment],” he said. “She would have been getting

farther ahead than any of the other federal courts in ruling what is

excessive solitary confinement without fact-finding during a trial.”

Grote

further noted that two of three similar cases challenging the duration

of solitary confinement in recent years have been found to have

sufficient cause to go to trial. Grote cited the summary judgment of the

Angola Three case as “a seminal opinion that laid out a roadmap for

Shoatz’s case.”

Shoatz,

has been in prison since 1972, when he was found guilty of a

first-degree murder that was part of a 1970 Black Liberation Army attack

on a Philadelphia police station, which resulted in the death of one

officer and the injury of another. In 1977, Shoatz and several other

prisoners overtook a cell block, injuring several guards with a knife,

and escaped from prison. While he was on the run, he went to the home of

a prison guard and eventually forced the guard, his wife, and child

into the woods, where he left them tied to a tree for several hours.

Back in prison after his re-apprehension, Shoatz was diagnosed with

paranoid-schizophrenia and depressive disorder and transferred to

Fairview State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. In 1980, he was able

to briefly pull off an escape from Fairview. When he was caught and put

back in prison, he began the first of his many long stints in solitary

confinement.

Shoatz

served two years in solitary confinement, from 1980 to 1982, until a

hunger strike that he and others in solitary confinement had organized

resulted in their release back into the general prison population.

However, his time outside of solitary was short lived. Back with the

general prison population, Shoatz began peacefully organizing with the

Pennsylvania Association of Lifers, attempting to get family members of

imprisoned people to lobby their state legislature to repeal life

without parole sentencing. One day in early 1983, Shoatz was named

interim president of the Lifers group, and was placed in solitary

confinement that night. Save for a nineteen month period from 1989 to

1991, Shoatz was kept in solitary confinement from that night until

2014.

While

in solitary, Shoatz was kept in a 7 x 12-foot cell in the Restricted

Housing Unit (RHU), an official euphemism for the block of cells used

for solitary confinement. Rubber strips surrounded the sides and bottom

of the cell door, effectively making his cell a sensory deprivation

chamber. The light of this cell remained on 24 hours a day, a practice

that Dr. James Gilligan, a psychiatrist serving as an expert witness

before the court, called “a well-known method of torture,” in his

declaration for the court. Prisoners in the RHU were prevented from

talking to each other, increasing the extreme social isolation beyond

that which is inherent in physical isolation.

Shoatz

was only allowed out of his cell for one hour a day, five days a week,

to exercise in a cage not significantly larger than a cell. This limited

recreation time required an intrusive strip search, which made Shoatz

anxious and caused him to rarely leave his cell during the small window

of time he was afforded to do so. He was also moved to a different cell

every thirty to ninety days. Shoatz wrote in his declaration for the

court, that “this increased my anxiety because I could never settle into

one place, and nobody ever told me why I was being moved. I also had

heightened anxiety because I was concerned that my property would be

taken during cell transfers, since it was searched upon leaving one cell

as well as when entering the next, and periodically items such as

approved reading materials and my own writings would be confiscated

during cell transfers.”

Through

the twenty-two consecutive years of solitary, Shoatz’s mental health

deteriorated tremendously, according to evidence presented in the

lawsuit. Dr. Gilligan concluded that years of extreme isolation and the

specific conditions of his time in solitary confinement led to a

menagerie of mental health problems. Shoatz’s mental health issues have

continued to persist since his release back into general prison

population, and include chronic depression, despair, intermittent

suicidal ideation, problems concentrating, short-term memory loss, and

insomnia. During the last six years he was in solitary confinement, he

could not sleep for more than four hours a night. Despite his apparently

deteriorating mental health, entire decades passed without the prison

giving Shoatz a mental health evaluation.

The

extreme isolation, Shoatz claims, also left him emotionally numb and

unable to form intimate relationships. Though he is no longer confined

to his cell, he rarely leaves unless he is required to do so. Speaking

during his evaluation about his time in solitary, Shoatz told Dr.

Gilligan, “I was infantilized for so long. I had to deal with very few

people. I developed no skills as to how to be in a relationship. I felt

relief from the ending of my relationship with [his former fiancé].

Nothing painful – I just don’t care.”

In

2004, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections created the Restricted

Release List (RRL), which kept those with RRL status in solitary

indefinitely. The list also prevented anyone placed on the list from

being released from solitary confinement in the RHU without the DOC

Secretary’s approval. For the secretary to consider this approval, the

prison’s warden had to recommend him for release. A grievance committee

heard from Shoatz every one to three months, but they only had the

ability to make minor changes, like providing an extra blanket to a

prisoner. Neither the committee, nor anyone else, ever provided Shoatz

with a rationale for his continued solitary confinement in RHU. Shoatz’s

lawyers called the review system “seriously Kafkaesque.”

Still,

each time he met with the committee, Shoatz asked to be released from

solitary confinement. Despite being made aware of Shoatz’s condition,

including meeting with Shoatz’s daughter in 2012, Secretary Wetzel never

reviewed Shoatz’s RRL status from 2004 until his release from solitary

in 2014. In a document provided to the court, a 2012 SCI – Greene staff

document admitted that at 68 years old, Shoatz himself was not a serious

escape risk, but argued that his history of political organizing “poses

a substantial risk to the staff and the security of our institution.”

Standard

international rules for the treatment of prisoners have been in place

since the 1950s, but that the UN clarified them last year, laying out

what are now called the Nelson Mandela Rules. Juan Mendez, the UN

Special Rapporteur on Torture, who also provided expert witness in

Shoatz’s suit, told Solitary Watch that under international and US law,

that more than fifteen days in solitary would constitute cruel and

unusual punishment, but that the duration of Shoatz’s stay in solitary

“violates international law and is definitely torture.”

Judge Eddy is expected to shortly set a trial date for Shoatz’s suit, which will begin sometime later this year.

No comments:

Post a Comment