Will the Real Santa Claus Please Stand Up?

—

December 13th, 2013

We always think of Santa Claus

as an incredibly old man—positively ancient—but the fact is, he’s

exactly 150-years-old, born in 1863. Indeed, we might be thinking of

Santa’s predecessor St. Nicholas, who is far older, believed to have

been a Turkish Greek bishop in the 300s. But the first European winter

gift-bringer is even more of a geezer, going back to ancient Germanic

paganism and the Norse god Odin. When he wandered the earth, the deity

disguised himself as a bearded old man wearing a broad-brimmed hat and

cloak and carrying a traveler’s staff. He looked a lot like Gandalf the

Gray in “Lord of the Rings.”

Even in the early days, Santa had his vices.The gift-bringer showed up during the 12-day winter festival known as Yule, where it was a tradition to burn a whole tree, from bottom up. (This evolved into the smaller “Yule log” we know today.) Children would leave hay in their shoes for Odin’s eight-legged horse and find it replaced with treats the next day. As Europe became Christianized, these beliefs were absorbed into the Christian faith, and St. Nicholas, celebrated on December 6, was bestowed with the gift-bringer mythology.

As the legend goes, Nicholas of Myra, located in Asia Minor at the time, was born a very rich man, who eventually gave away every penny he had. His neighbor, on the other hand, was so poor that he couldn’t even afford the dowries to marry off his three daughters. When the first daughter reached marrying age, Nicholas snuck up the roof of the family’s house and dropped a bag of gold down the chimney, which fell into a stocking hung by the fireplace to dry. He did this again for the second daughter. The father finally caught him the third time, and humble Nicholas asked him to keep it a secret, as he wasn’t looking for praise.

Top:

A religious icon of Saint Nicholas of Myra, believed to be a generous

4th-century bishop in Asia Minor. Above: Green-coated Father Christmas

emerged in Renaissance-era England as the embodiment of the holiday.

This cheerfully generous and cuddly grandpa served as a comforting Santa figure during the Depression and World War II.Proponents of the Protestant Reformation, starting in 1517, were eager to abolish the Catholic saints from Christian worship—but the Dutch were unwilling to give up their beloved Sinterklaas. Thanks to Martin Luther’s campaign against Saint Nicholas, a good deal of European Protestants simply adopted the cherubic blond-haired blue-eyed Christ Child, or Christkindl, as the gift-bringer. Eventually, this character was absorbed into the St. Nicholas mythology, too, as “Kris Kringle” became another of his names.

In 15th-century England, “Nowell” or “Sir Christmas” emerged as the personification of Christmas, a man who delivered the story of Christ’s birth. By the 18th century, he evolved into a green-cloak-wearing gift-bringer known as “Father Christmas,” a kindly old gentleman full of good cheer, whom Puritans condemned for his Pagan roots. After all, Father Christmas was often depicted bringing the Yule tree, like Odin. The Puritans came to America hoping to establish a holy Christmas celebration free of Father Christmas or St. Nicholas, but the Dutch brought their Sinterklaas to New Amsterdam, now known as New York.

Belsnickel,

one of St. Nicholas’s helpers in the Germanic tradition, checked on

children’s behavior before Christmas. Here he carries switches in one

hand and a feather tree in the other.

Aside from Belsnickel, both Saint Nicholas and Father Christmas were generally depicted as tall, slender men. That all changed in 1809, when American writer Washington Irving published a parody of the Dutch community called “Knickerbocker’s History of New York.” In his book, he described their patron saint Nicholas as a short, roly-poly Dutchman with elfin features who smoked a long, slender pipe and drove a wagon above the trees.

Inspired

by “’Twas the Night Before Christmas,” magazine illustrator Thomas Nast

drew a chubby Old St. Nick in 1863 and gave him the name “Santa Claus.”

“His eyes — how they twinkled! His dimples: how merry,

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry;

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard of his chin was as white as the snow;

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath.

He had a broad face, and a little round belly

That shook when he laugh’d, like a bowl full of jelly:

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf, …”

But the fat man didn’t get the name “Santa Claus” until 1863 when Thomas Nast drew a series of illustrations for “Harper’s Weekly Magazine,” which ran until 1886. Nast, a man of Germanic heritage who may have been influenced by childhood stories of Belsnickel, gave his chubby little Santa a workshop, with a Christmas tree and stockings hanging on a fireplace. In England, this new red-wearing version of St. Nicholas soon melded with Father Christmas, who became an even more important figure for children. Children’s books were reissued with Santa Claus on the cover and in the title. Victorian manufacturers produced puzzles, board games, and jack-in-boxes with Santa themes. At the turn of the century, American illustrator J.C. Leyendecker furthered the image of a pudgy, red-suited Santa, as did Norman Rockwell, starting in the 1920s.

Famous

illustrator Haddon Sundblom first painted Santa Claus for Coca-Cola in

1931. His tall, heavy red-suited grandpa set the standard for portraying

Santa in the 20th century. (Via www.coca-colacompany.com)

This cheerfully generous and cuddly grandpa served as a comforting figure during the Depression and World War II. The sweet Santa mythology solidified with the 1939 Montgomery Ward children’s book about his ninth sleigh-puller, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” as well as the 1946 Gene Autry song, “Here Comes Santa Claus,” and the 1947 movie, “Miracle on 34th Street,” about one Mr. Kris Kringle. Rushton’s soft-bodied Santa dolls with rubber heads, with or without a Coke bottle in hand, grew popular in the late 1950s, as they represented a return to hope and innocence. Santa’s likeness has adorned countless objects from ashtrays to light-up, blow-mold lawn ornaments, and cocoa mugs to novelty brooches with a red light for his nose.

As early as 1919, American tobacco companies like Murad created ads showing Santa trading his pipe for cigarettes.

Despite what Fox News’ Megyn Kelly says, no one actually knows what skin color Nicholas of Myra had, or if he even existed in the first place. Except for the white beard, Old Saint Nick’s appearance has changed drastically throughout time. He generally took on the appearance of people in the communities who celebrated him—so because the American Santa mythology has roots in Dutch, German, and British traditions, he was traditionally portrayed as an old white man.

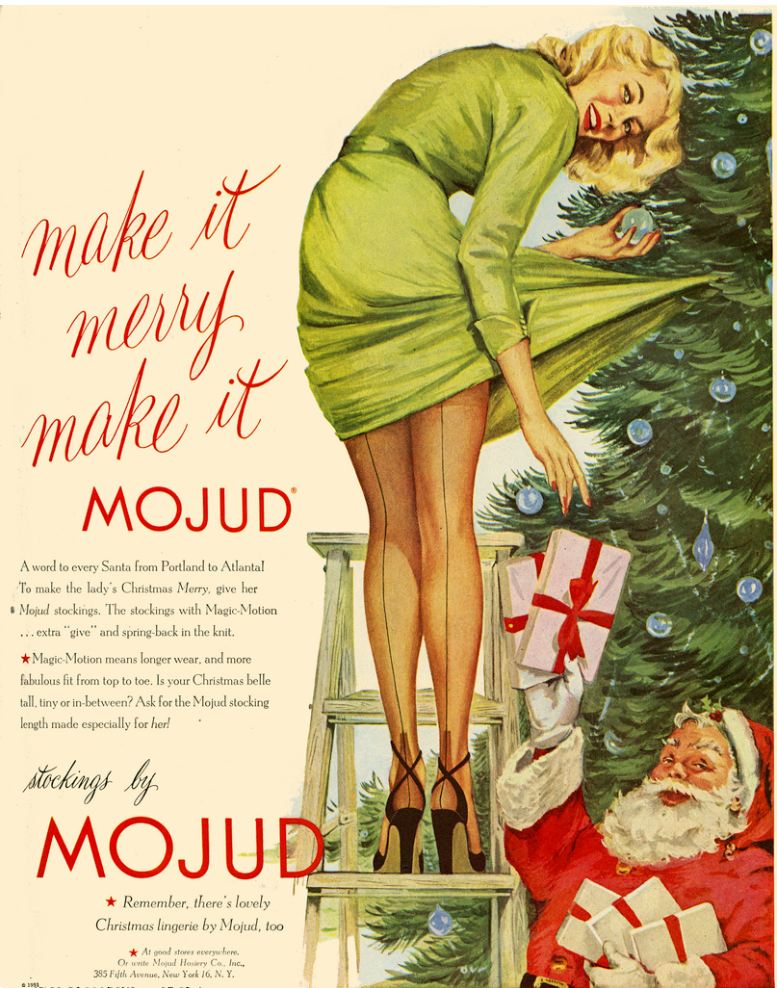

In

1951, American hosiery company Mojud produced this racy ad showing

Santa losing a bit of his innocence. Click image for a larger version.

After that, images of black Santa became more common and socially accepted, even though, as Slate’s Aisha Harris points out, most Santa iconography today still tends to fall in the “white-as-default” trap. Her solution: Make him a penguin. And why not? Looking at Santa’s history, it’s clear he can do and be anything we want him to.

“Esquire”

magazine lost an estimated $750,000 in advertising after it put

heavyweight boxing champ Sonny Liston on its cover in a Santa hat in

1963.

Those who fret about the so-called “War on Christmas” would like to go back to that pudgy, twinkly-eyed old elf driving adorable reindeer invented by Victorians and reimagined by Coca-Cola. They don’t want to see any computers, penguins, or black men as the embodiment of the gentle and generous Christmas Spirit, much less a white Santa saddled with the vulgar humanity seen in cynical modern films like “The Santa Clause,” “Bad Santa,” and “Fred Claus.” But the truth is, their “good Santa” sold out to big tobacco and gave in to lecherous thoughts a long time ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment